Parallel Practice

Why my mom had to hide (from me) in the bathroom

Hi everyone,

I came here to talk about an essay I wrote for The Rumpus about embroidery, parenting, and attention. It feels a bit cringey to do this, but I’m proud that it came out and I want to share it. I am a cat who has caught a bird and must leave it on your doorstep:

🐈 “How to Break a Sentence,” The Rumpus 🐈

The essay appeared in The Rumpus’s Parallel Practice column, a series on the practices that develop alongside writing. I love the idea of a hidden mechanism that isn’t quite “the thing” but that moves alongside it and propels it.

I took up embroidery (and started writing about it) a couple years ago, when my husband and I lived in different states for months at a time because of his work in Texas and my return to grad school in NYC. When he had our daughter with him the separation was painful, but when I had her with me it was hard in a different way. For her too, in ways she was perhaps too young to fully articulate.

My daughter was 3 and then 4 and needed attention, as little kids do, as we all do. I was lucky to be at home with her at all, and also lucky to have a space in my mind that felt capable of making art. But I struggled through the weekends alone with a small child, especially in winter, when we were often sick and isolated. I started doing embroidery as a bit of trickery. It was an escape hatch that allowed me to be with my daughter and still carry my own thoughts through to some kind of completion.

It’s not like it’s easy to sew while being constantly interrupted—it’s more that seeing the embroidery take form in my hands helped us both—my daughter and I—to leave a little space for it. I could make something without withdrawing from my daughter.

After publishing the essay I got some private messages from parents who said these dynamics were familiar to them. These filled me with joy. But of course this wasn’t enough for me, and I insisted my mother tell me what she thought of it too.

In my head I had already begun to pen a rebuttal to my own work: Who was I, mother of one, to complain of the demands of parenting? Who was I, a student without a full-time job, to claim I didn’t have enough time to make art? I had written the essay over a year ago, and now I wanted to pick a fight with the narrator. I wanted my mom—who had four kids and worked a full-time, low-wage job while also single-parenting—to say I didn’t know what I was talking about.

But of course that’s not what happened. We remembered our own time together, when I was 3 and 4. She told me of her own favorite sleights of hand for dealing with a child’s need for constant attention, a parent’s desire to have perhaps five minutes of uninterrupted thought. (A lot of hiding in bathrooms.)

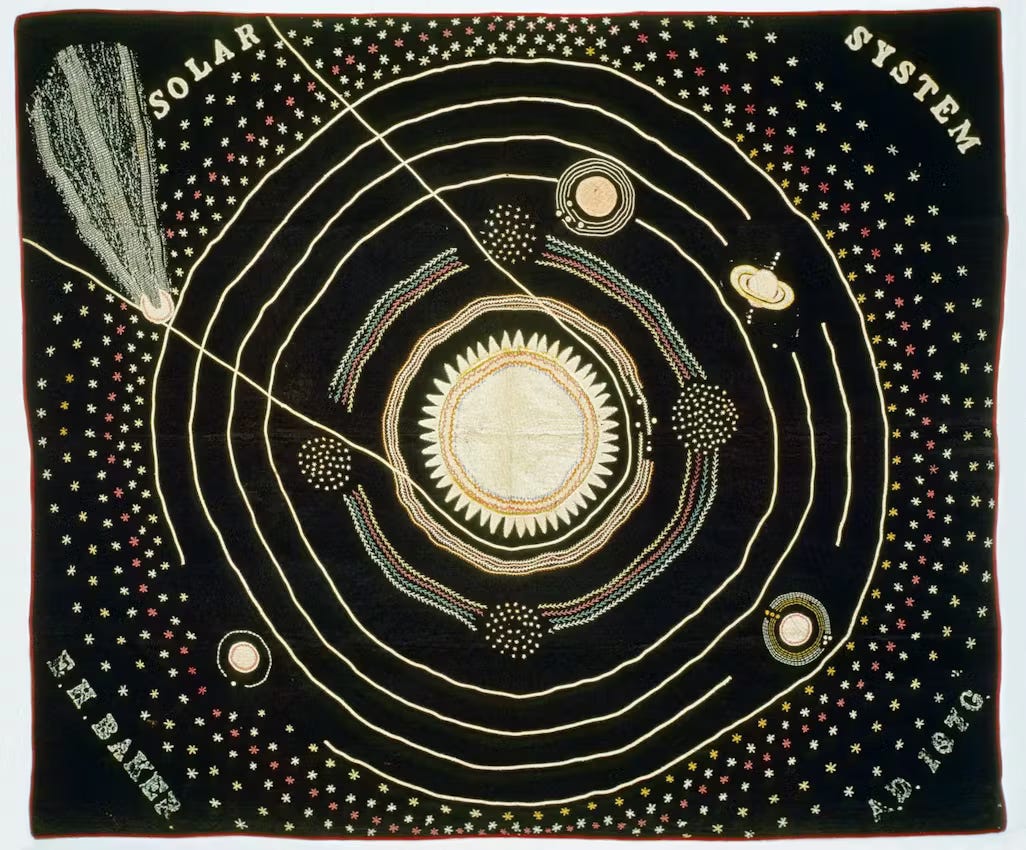

The essay in The Rumpus is about this project I cooked up in which I used embroidery to write, but without using language at all. A bit esoteric, but I was really into it. At the same time I was sewing a series of little pouches to give as gifts. They did not feature expert-level sewing, but I loved making them. And they were easier to interpret than my embroidered “sentences”—though they still did some kind of storytelling. I thought this dandelion one in particular had a narrative:

I’ve been working on a whole book about mothers and daughters, ghosts, and four generations of women in my Texas family. A literary agent asked me recently, with a look of horror, if I meant metaphorical ghosts or real ghosts. I couldn’t tell which was the right answer, so I said the truth: “Both, but it depends how you interpret ‘real,’ what kinda thing you go in for.” Her cringe deepened. It was interesting to me she zeroed in on the ghost aspect, which usually garners an “oooh, my house is haunted too,” and not on the mother aspect, which is usually more divisive. (See: Against Motherhood Memoirs, an essay that is actually against motherhood memoir marketing, imo)

I could keep looking for proof that the writing is silly, that my little essay was superfluous too. But I believe in it anyway. That was the real heart of the embroidery writing—no matter how much I theorize, I can’t escape the urge to convert experience into story.

There’s been a lot of equivocating—in light of our political situation—over the value of making things. Should artists really stay committed to their obsessions at a time like this? See Elif Batuman: In Dark Times, What Is the Artist For?

My friend promised recently on his own Substack not to write for the sole purpose of creating content, which is an empty commodity (my words), but only when he has something to say. I love this sentiment. The problem is that I almost always have something to say. At any given moment, I’ve got 2,000 words locked and loaded.

Anyway, here’s the beginning of my piece in The Rumpus. I hope it resonates:

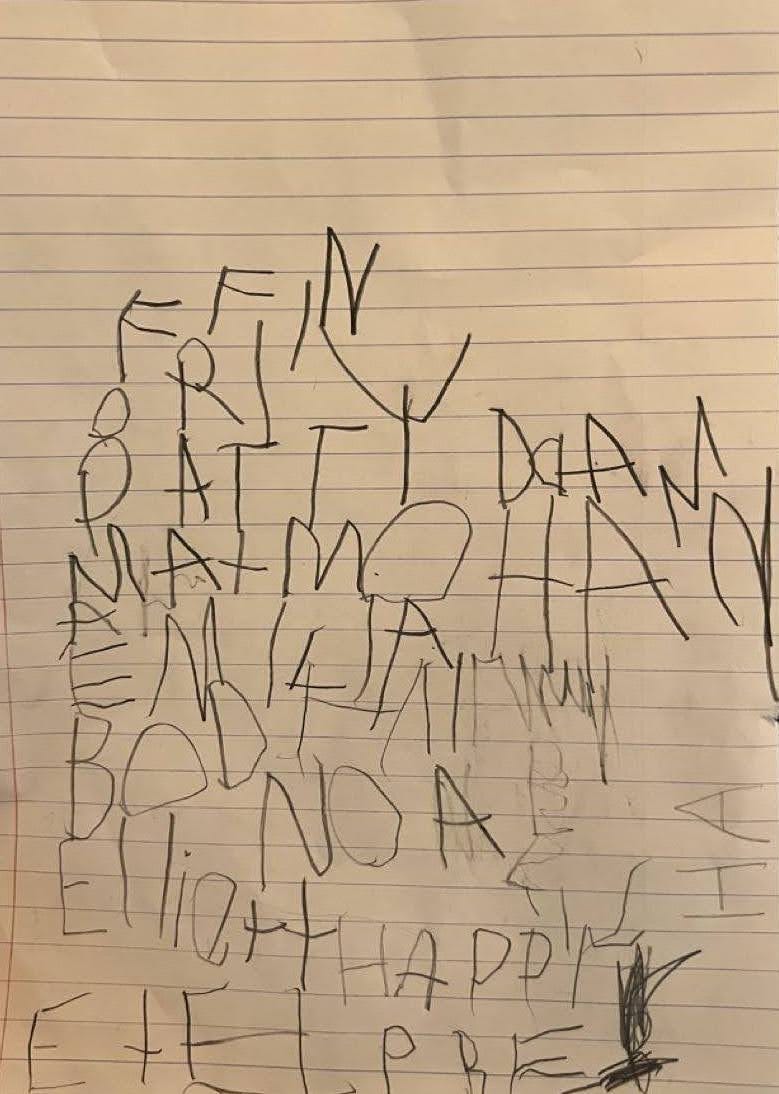

I was at the kitchen table with my four-year-old when I had the idea to represent a sentence through embroidery. I’d been reading Renée Gladman and looking at her Prose Architectures, a book of pen drawings that Gladman intended, as I read on the publisher’s website, “to free language from constraint.” The drawings arc and scribble but never fall into the shapes of letters or words. They evoke city skylines more than sentences, and yet they depict movement. They do the work of containing something.

More photos over there too. ;)